Catalog Essay by Kara Rooney for “Reflections on Everyman: The Work of Jan Sawka,” an exhibition curated by Evonne M. Davis and Hanna Maria Sawka, Sept. 12 – Dec. 14, 2013, Gallery Aferro, Newark, NJ.

Jan Sawka: The Edge of Periphery

The year is 1976. Poland, having languished for decades under the authoritarian rule of the Soviet controlled People’s Republic, is in the midst of political revolution. Jan Sawka, at the time a leading artist for the Polish Poster School and full-time set designer for the avant-garde theater groups of Krakow and Warsaw, is labeled a ‘dangerous’ oppositionist and forced into exile. He and his young family spend a year in France with Sawka as one of the first Artists in Residence at the just-opened Centre Georges Pompidou, before embarking on their longer journey to New York, the city the artist would, over the course of the next forty years, come to call home.

During this time, Sawka created hundreds of paintings, sculptures, prints, illustrations and site-specific commissions, projects as varied as his long-standing editorial work for the New York Times to the monumentally scaled sets and graphics he designed for the Harold Clurman, Jean Cocteau Repertory and Samuel Beckett theaters, along with music icons The Grateful Dead and Steve Winwood. His exceedingly prolific output, riddled with vibrantly hued iconography and a plethora of actors, reflects uncompromisingly upon the human condition. Undoubtedly influenced by the turbulent legacy of his homeland and often logging more than 18 hours per day in his studio, Sawka’s staunch commitment to the visual articulation of experiential inquiry—in all its manifestations: political, cultural, social and individual—belies the core of his life’s work.

Sawka was a Baudelarian ‘man of the world,’ absorbing the nuanced details of each place he encountered: his native Poland, America, Japan and numerous other exotic locales where his work would ultimately take him. These experiences culminated in the polytropic expression of an otherworldly vision, one in which hope and resistance met with equal regard. Of his work, Sawka states, “I have no idea which trend of art I represent. Nothing interests me less.” Downright impossible to categorize, his is a balancing act between the utterances of a patriot/ex-patriot, an insider/outsider, who continuously slips the trap of classification.

If there were an organizing principle to be found in Sawka’s imagery, however, it would have to be the diverse variety of portraits that adorn the surfaces of his highly intricate sculptures, prints and paintings. Often wrapped or bound, physically quarantined from the outside world via rope and other framed apparati, these trussed figures signify the image of oppression. Often anonymous, they represent neither one individual nor many but the collective face of society at large, along with its hypocritical affectations of structure and rule, freedom and sovereignty, individual versus communal thought. These polarizing forces are not only externally inflicted but internally driven, as seen in numerous of Sawka’s psychologically charged poster designs and prints from the 1980s, works that coincide with his time as an artist in residence at the Pratt Manhattan Center and his native Poland’s anti-Communist Solidarity period.

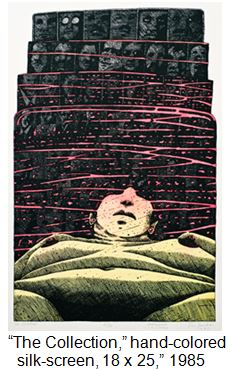

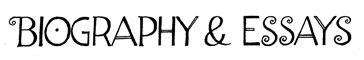

The Collection, the first in a suite of eight hand-colored silkscreens from 1985, for example, features the hulking figure of a woman reclined and nude as if in slumber. Hovering in space above the subject’s head are dozens of smaller, tightly cropped black and white portraits, their identifying features obliterated by densely etched lines and whirling horizontal striations of pink neon. The effect is one of dreamlike chaos where the viewer struggles to differentiate between the imagined state of the work’s protagonist and the potential reality of her predicament. The Collection, the first in a suite of eight hand-colored silkscreens from 1985, for example, features the hulking figure of a woman reclined and nude as if in slumber. Hovering in space above the subject’s head are dozens of smaller, tightly cropped black and white portraits, their identifying features obliterated by densely etched lines and whirling horizontal striations of pink neon. The effect is one of dreamlike chaos where the viewer struggles to differentiate between the imagined state of the work’s protagonist and the potential reality of her predicament.

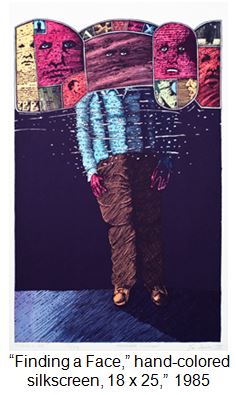

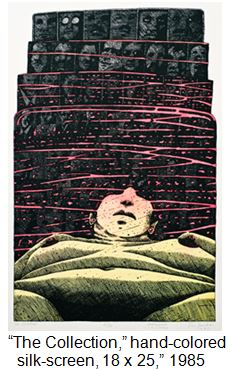

Finding a Face, also dated 1985, features a similar scenario except here the subject’s visage is shrouded in the blurred context of a framed ‘other.’ Successive storyboard cells divide the upper quadrant of the image into multiple portraits hemmed in by text and line. Partial profiles and cropped views of facial features foreground a sequentially unfolding narrative that places pressure on conventional reading, while the lower half of the image showcases a solitary form, leaning slightly off-balance in the surrounding darkness. The figure’s fragile physical state, at risk of being erased by

Finding a Face, also dated 1985, features a similar scenario except here the subject’s visage is shrouded in the blurred context of a framed ‘other.’ Successive storyboard cells divide the upper quadrant of the image into multiple portraits hemmed in by text and line. Partial profiles and cropped views of facial features foreground a sequentially unfolding narrative that places pressure on conventional reading, while the lower half of the image showcases a solitary form, leaning slightly off-balance in the surrounding darkness. The figure’s fragile physical state, at risk of being erased by

the plethora of lines that intersect his body, forces us to question his position in relation to reality, fiction and fact. But whether peripheral or internalized forces are at work in each of these pieces is of little consequence in that either interpretation leads us down the same path. Reality formation is what is at issue here. Objects exist in the physical world for which there is empirical evidence, yet how we, as individual members of culturally conditioned societies, choose to interpret that information is largely subjective. And herein lies the true achievement of Sawka’s work: its human accessibility. We identify with Sawka’s subjects’ implicit oppression and psychological duress, with their feelings of entrapment, intellective overload and the paralyzing sense of confusion lurking in double-tongued speech and realpolitik. Such conflict is at the core of revisionist thought. With image after image, Sawka performs translations of such cultural signifiers into code, and code into cultural signifiers, all within a freshly expanded field of complex inter-connectionism.

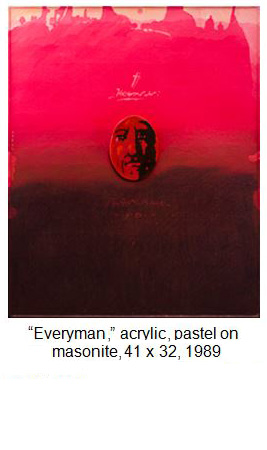

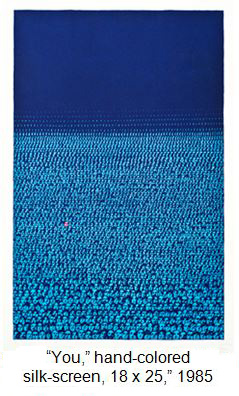

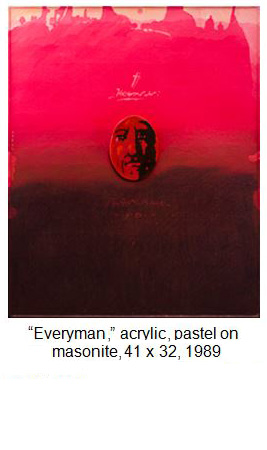

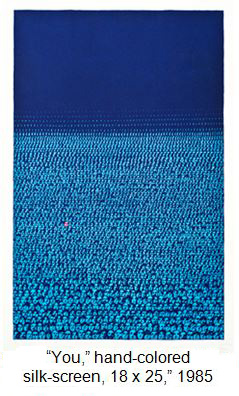

This curious commingling of the social and the particular finds a distinct clarity of voice in You (1985) and Everyman (1989), where the artist forces us, through diametrically opposed tactics, to consider the futile nature of individual hierarchy. You presents the viewer with thousands of portraits, a sea of faces jammed together, their numbers so dense that the receding horizon of bodies only hesitantly retreats into a background expanse of cerulean blue. Towards the center left of the composition one face stands out, nondescript save for his fleshlike coloring. Conversely, Everyman depicts a

This curious commingling of the social and the particular finds a distinct clarity of voice in You (1985) and Everyman (1989), where the artist forces us, through diametrically opposed tactics, to consider the futile nature of individual hierarchy. You presents the viewer with thousands of portraits, a sea of faces jammed together, their numbers so dense that the receding horizon of bodies only hesitantly retreats into a background expanse of cerulean blue. Towards the center left of the composition one face stands out, nondescript save for his fleshlike coloring. Conversely, Everyman depicts a

single floating visage, completely devoid of compositional embellishment except for an indistinguishable word written in delicate cursive above the figure’s head. A background landscape of hotly keyed fuschia lends the work an explosive air. Hopeful or fatalistic, the one who changes the world or the one who idly believes he is different than the rest—these works could represent either extreme. It is in such contradictory presentations that we find Sawka himself: the cunning trickster who seeks to mediate oppositions by occupying the field between polarities.

single floating visage, completely devoid of compositional embellishment except for an indistinguishable word written in delicate cursive above the figure’s head. A background landscape of hotly keyed fuschia lends the work an explosive air. Hopeful or fatalistic, the one who changes the world or the one who idly believes he is different than the rest—these works could represent either extreme. It is in such contradictory presentations that we find Sawka himself: the cunning trickster who seeks to mediate oppositions by occupying the field between polarities.

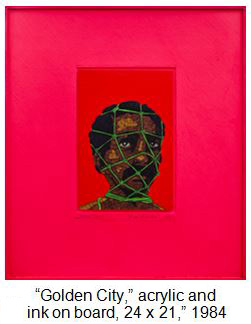

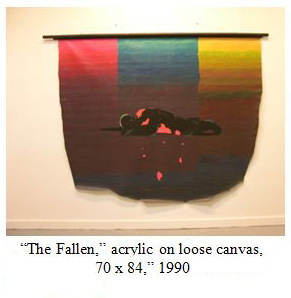

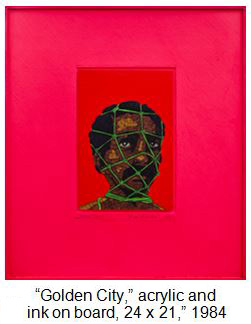

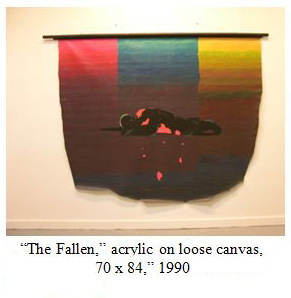

But while Sawka’s work consistently denies categorization as creative propaganda he did at times dedicate himself to working within the confines of such parameters. The vibrantly hued painting Golden City (1984), for example, illustrates Sawka’s artistic response to apartheid, while his 1990, The Fallen, is undeniably direct in its political aims. Here the words of the Russian Constructivist poet-painter Vladimir Mayakovsky, artist Sawka was

But while Sawka’s work consistently denies categorization as creative propaganda he did at times dedicate himself to working within the confines of such parameters. The vibrantly hued painting Golden City (1984), for example, illustrates Sawka’s artistic response to apartheid, while his 1990, The Fallen, is undeniably direct in its political aims. Here the words of the Russian Constructivist poet-painter Vladimir Mayakovsky, artist Sawka was

no doubt aware of having been trained by institutions of Communist rule, come to mind: “the streets our brushes, the squares our palettes.” Such commitment to the articulation of a wider vision of political awareness—including private cultural, ecstatic or numinous themes accessible through the subjective realm of each individual—reveal in considered detail, the full spectrum of Sawka’s social-political knowing. no doubt aware of having been trained by institutions of Communist rule, come to mind: “the streets our brushes, the squares our palettes.” Such commitment to the articulation of a wider vision of political awareness—including private cultural, ecstatic or numinous themes accessible through the subjective realm of each individual—reveal in considered detail, the full spectrum of Sawka’s social-political knowing.

His many sculptures are just as ambiguous in their intellectual conceit. Despite an intensive traditional education, the spirit of the 60s formed Sawka’s artistic voice. Thankfully, his sculptural work retains lively aspects of that psychedelic time: hallucinogenic scenarios frequently butt up against energetically colored accoutrement, and an off-beat use of materials—wood, plaster, picture frames, twine and acrylic paint—deny the postmodernizing slickness of Minimalist gesture. Bucking all ‘contemporary’ notions of sculptural form, Sawka continued to experiment well into his later years with the bust, producing viscerally layered works such as Torso I (Three Generations) (1998), Torso II (2001), Torso III, Torso IV (both 2004) and Torso V (2003). All feature variations on the enmeshed portraits of his prints and drawings, yet their translation into three-dimensions adds a fleshly sentience to his carefully constructed iconography. The artist’s formal background in architectural engineering is most readily visible in these images as well, where delicate scaffolding plays with the division of space between viewer and object.

It is often said that to escape the trap of mere opposition, the invention of some third thing is required, a portal perhaps, through which we might encounter the world anew. Sawka’s is such a story about reading the world. His vast array of work, multivalent in meaning and freighted with historical paradox, forces us to question the ultimate sense and authority of the structures we erect in glorious and proud detail. These boundaries and perimeters often cost us dearly, boxing us in, limiting our proclivity and desire for creative thought. Hence it seems little wonder that as we watch them crumble in the mythology of Sawka’s carefully reinvented world, we register a certain glee. The portal is open. How we choose to traverse its threshold is ours to decide.

- Kara L. Rooney

* Kara L. Rooney is a Brooklyn based artist, writer and curator. She currently serves as an Associate Art Editor for the Brooklyn Rail.

Catalog Essay by Kara Rooney for “Reflections on Everyman: The Work of Jan Sawka,” an exhibition curated by Evonne M. Davis and Hanna Maria Sawka, Sept. 12 – Dec. 14, 2013, Gallery Aferro, Newark, NJ.

________________________

The Collection, along with You, August 6, 1985, Four Seasons and Number 4 all belong to a series of prints that are considered one artwork. The most well-known edition of Sawka’s individually hand-colored drypoint engravings is titled A Book of Fiction. The edition of 25 prints and 8 artist’s proofs were printed as a coffee table book by Clarkson and Potter, for which it won first place at the Frankfurt Book Fair and received the NY Times’ Book of the Year Award in 1986. Sawka’s drypoint engraving prints represent the largest collection of a single artist’s works in the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

Sawka completed two Master degrees: one in Painting and Printmaking from the Wroclaw Fine Arts Academy and the other in Architectural Engineering from the Institute of Technology in Wroclaw.

|

The Collection, the first in a suite of eight hand-colored silkscreens from 1985, for example, features the hulking figure of a woman reclined and nude as if in slumber. Hovering in space above the subject’s head are dozens of smaller, tightly cropped black and white portraits, their identifying features obliterated by densely etched lines and whirling horizontal striations of pink neon. The effect is one of dreamlike chaos where the viewer struggles to differentiate between the imagined state of the work’s protagonist and the potential reality of her predicament.

The Collection, the first in a suite of eight hand-colored silkscreens from 1985, for example, features the hulking figure of a woman reclined and nude as if in slumber. Hovering in space above the subject’s head are dozens of smaller, tightly cropped black and white portraits, their identifying features obliterated by densely etched lines and whirling horizontal striations of pink neon. The effect is one of dreamlike chaos where the viewer struggles to differentiate between the imagined state of the work’s protagonist and the potential reality of her predicament.  Finding a Face, also dated 1985, features a similar scenario except here the subject’s visage is shrouded in the blurred context of a framed ‘other.’ Successive storyboard cells divide the upper quadrant of the image into multiple portraits hemmed in by text and line. Partial profiles and cropped views of facial features foreground a sequentially unfolding narrative that places pressure on conventional reading, while the lower half of the image showcases a solitary form, leaning slightly off-balance in the surrounding darkness. The figure’s fragile physical state, at risk of being erased by

Finding a Face, also dated 1985, features a similar scenario except here the subject’s visage is shrouded in the blurred context of a framed ‘other.’ Successive storyboard cells divide the upper quadrant of the image into multiple portraits hemmed in by text and line. Partial profiles and cropped views of facial features foreground a sequentially unfolding narrative that places pressure on conventional reading, while the lower half of the image showcases a solitary form, leaning slightly off-balance in the surrounding darkness. The figure’s fragile physical state, at risk of being erased by  This curious commingling of the social and the particular finds a distinct clarity of voice in You (1985) and Everyman (1989), where the artist forces us, through diametrically opposed tactics, to consider the futile nature of individual hierarchy. You presents the viewer with thousands of portraits, a sea of faces jammed together, their numbers so dense that the receding horizon of bodies only hesitantly retreats into a background expanse of cerulean blue. Towards the center left of the composition one face stands out, nondescript save for his fleshlike coloring. Conversely, Everyman depicts a

This curious commingling of the social and the particular finds a distinct clarity of voice in You (1985) and Everyman (1989), where the artist forces us, through diametrically opposed tactics, to consider the futile nature of individual hierarchy. You presents the viewer with thousands of portraits, a sea of faces jammed together, their numbers so dense that the receding horizon of bodies only hesitantly retreats into a background expanse of cerulean blue. Towards the center left of the composition one face stands out, nondescript save for his fleshlike coloring. Conversely, Everyman depicts a